“Behind almost every treatment, medicine, therapy & medical device…are millions of people who have volunteered to take part in clinical trials.”

The Impact Clinical Trials Have on All of Us – CISCRP

What is a cavernous malformation clinical trial?

A cavernous malformation clinical trial is a study using human volunteers that seeks to find out if a specific treatment for cavernous malformation is safe and effective. Clinical trials are:

1) Required before a treatment can be approved by the United States FDA.

2) Conducted after a treatment has been shown to be safe for use in animals.

3) Carefully planned with safeguards to reduce risk to participants.

Why are clinical trials conducted? Why can’t I just start using treatments that work in animals?

A clinical trial allows researchers to measure and record the effects of new treatments on humans in a systematic way. Many treatments have been shown to be safe and effective in animals but not in humans. A clinical trial is the only method we can use to know whether or not a treatment is safe and effective in people. Without a clinical trial, we would have only anecdotal evidence – case studies of one or just a few people – that may reflect changes in the illness that actually have nothing to do with the treatment. It is only by testing the treatment in enough people under controlled conditions that we can be sure it works.

What do we learn from clinical trials?

Clinical trials allow us to learn:

1) Whether a new treatment is safe

2) Whether a new treatment is more effective than other available treatments

3) How much of a new treatment is needed to have the desired effect – the dose, frequency, etc.

4) Whether a new treatment has unintended side effects.

What kinds of treatments may be tested in cavernous malformation clinical trials?

There are several kinds of treatments that may be tested in a cavernous malformation clinical trial, including:

1) New medications that are under development and have not yet been approved for use for any other illness.

2) Repurposed medications or supplements

- Prescription medications that remain under patent for another indication.

- Prescription medications that are no longer patented and therefore are available as generic medications, possibly from more than one manufacturer.

- Supplements like vitamins or other medications/substances available without a prescription. These “alternative treatments” can become accepted treatments if they are proven safe and effective in clinical trials.

3) Other treatments, like diet or lifestyle changes.

4) Non-invasive or invasive surgical treatments like stereotactic radiosurgery, focused ultrasound, and autologous stem cell implantation.

Testing medications that are already known to be safe and effective for other illnesses seems like a great idea. Why aren’t we doing more of this kind of testing?

The short answer for medications that are already off-patent is an economic one. Because these medications are no longer owned by a single company, no for-profit entity will take them to trial because there is no money to be made by doing so. Trials of these medications must be funded with government or foundation grants – there is much less of this funding to go around as it’s reliant on taxes or charitable donations.

Additionally, for-profit companies that have treatments under patent for other illnesses that might also be effective for cavernous malformation must weigh the risks and benefits. There are two considerations: they must believe the money they invest to try their treatment on cavernous malformation will be justified by their product sales, and they must weigh the risk of a safety issue arising in a cavernous malformation trial that could harm the reputation of the treatment for use in other indications, including the original indication.

What will treatments for cavernous malformation target?

Treatments for cavernous malformation may target different features of the illness. A cavernous malformation treatment may:

1) Reduce the risk of re-hemorrhage.

2) Reduce the leakiness of cavernous malformation vessels. This may have a secondary effect of reducing inflammation and resulting hemorrhage.

3) Prevent a small cavernous malformation from growing larger.

4) Shrink an existing cavernous malformation.

5) Prevent the development of more cavernous malformations in the hereditary form of the illness.

Why are the first treatments being tested targeted at reducing the risk of re-hemorrhage?

1) Hemorrhage is the most debilitating and worrying possibility of a cavernous malformation. We know that hemorrhage causes symptoms and disability.

2) We also know cavernous malformations are most likely to re-hemorrhage within 2-3 years of a first hemorrhage. Knowing this allows for the design of short trials that require fewer participants, making the trials economically feasible. Trials would seek to enroll those who had a recent symptomatic hemorrhage.

3) A treatment that can prevent re-hemorrhage may also address some of the other targets, like leakiness. However, we need to start with hemorrhage, because it is the target that will get us to approval most efficiently.

4) Although seemingly self-evident, we actually don’t know yet whether having more lesions or larger lesions causes more symptoms. The FDA will not support trials or approve a treatment unless it has clinical benefit, which means reducing or preventing symptoms that a patient may experience. They will not support trials or approval of medications that aim to reduce or slow the development of lesions until we have proof this is tied to clinical outcomes.

5) We don’t yet have a treatment ready for trials that will shrink lesions and make them go away.

How is symptomatic hemorrhage defined?

In 2008, the Alliance to Cure Cavernous Malformation Scientific Advisory Board, led by Dr. Rustam Salman, wrote Hemorrhage from Cavernous Malformations of the Brain: Definitions and Reporting Standards, published in the journal Stroke. To qualify as symptomatic hemorrhage, there must be evidence of fresh bleeding visible on MRI as well as a functional neurological deficit. Bleeding without symptoms or symptoms without evidence of bleeding does not qualify.

What other ways may we measure whether a treatment is working?

Researchers are working to validate biomarkers that might become indicators. A biomarker is a measurable biological characteristic that correlates with changes in a disease state. The changes could indicate the presence of the illness (diagnostic), predict the worsening of the illness in the future (predictive), or reflect a change in the severity of symptoms (progression). For cavernous malformation, researchers are working to validate:

1) Biomarkers in MRI imaging that look at the leakiness of blood vessels and the very specific amounts of iron, a blood breakdown product, deposited in or near a cavernous malformation lesion. Validation means that changes in leakiness or iron on MRI must correspond to changes in symptoms.

2) Blood tests that may predict who will bleed in the future.

3) Blood tests with values that vary depending on bleeding activity, measuring progression.

4) Diagnostic urine tests that show whether or not someone has a cavernous malformation.

What about simply asking me if I feel better?

Researchers are developing a survey to measure our patients’ experience of the illness, which will be called the CCM-Health Index. If the survey is approved by the FDA, it will allow patients to report their symptoms and have this information be taken into account when judging the effectiveness of treatment.

Who will participate in the first trials?

Participation in a trial will be determined largely by the anticipated effect of the medication. If a medication is thought to reduce re-hemorrhage, participants will be those who have had a recent prior hemorrhage. If the medication targets some other feature – new lesion development, lesion growth, overall symptom progression, etc. – trials will be designed to enroll individuals who are most likely to show whether or not a medication is having an effect.

Will some people in a trial receive a placebo?

Yes, for most clinical trials to demonstrate whether a treatment is safe and effective, some participants will receive a placebo – a look-alike treatment that does not contain the active ingredients of the medication – or will be part of an untreated control group. In some cases, if a treatment has been found to be super-effective, a trial is ended early so everyone can use the treatment. In most cases, the difference in outcome between those who receive treatment versus those who receive no treatment is not so dramatic. It must be determined statistically, so a placebo group is needed for comparison. Neither the participants nor their doctors know who is receiving a placebo or who is receiving the treatment until the end of the trial. Once the trial is over, if the treatment is effective and approved by the FDA, everyone can begin to use it.

What is the benefit of participating in a clinical trial?

The investigational treatment studied in a clinical trial may or may not benefit you personally. The benefits of participating in a clinical trial may include:

1) Helping patients like you by contributing to medical research and treatment advances.

2) Gaining access to cutting-edge research.

3) Receiving expert medical consultation for the condition being studied, since doctors conducting clinical trials are often specialists in the disease areas being studied.

What are the risks associated with clinical trial research?

Possible risks of participating in a clinical trial include:

1) Clinical trials study investigational treatments, therefore some information about the treatments is unknown.

2) The investigational treatment you receive may not be effective, or may cause unpleasant, serious, or even life-threatening side effects.

3) Participating in a clinical trial may require a time commitment or a financial commitment.

Who is protecting me?

To protect the rights and welfare of clinical trial participants, US federal agencies, including the FDA and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), oversee much of the medical research in the US. Federal agencies inspect individuals and institutions conducting clinical trials.

Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) oversee the centers where clinical trials take place. IRBs review and approve protocols to make sure that clinical trials are ethical, and that volunteers’ rights are protected. They, too, are inspected by federal agencies. Also, some IRBs are accredited, much like hospitals can be accredited, and some research doctors and staff are certified as research professionals.

CISCRP, a non-profit organization dedicated to educating the public and patients about the importance of the clinical research process, has developed a clinical trial participant’s bill of rights.

What are the phases of a trial?

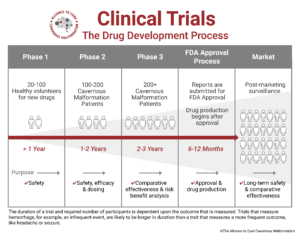

A clinical trial can consist of up to four phases. Some treatments will not require all four.

Phase I trials use healthy volunteers to test a treatment for the first time in human beings. The most important goal at Phase I is to establish that a potential new treatment is safe for humans. These trials are small, typically enrolling only 10-80 people.

Phase II trials evaluate a treatment’s safety and effectiveness in a group of participants who are affected by the illness (usually 100 to 300). This is also when the treatment dosage is established.

Phase III trials confirm a therapy’s effectiveness, monitor side effects, and compare it against the current standard treatments in a large group of people (around 1,000 to 3,000 is standard, but can be less for rare diseases). Phase III trials last longer and are usually conducted at multiple centers. Phase III trials are the final trials before FDA approval.

Phase IV trials are conducted after the treatment has received FDA approval and been brought to the market. These trials help further evaluate long-term side effects and potential new uses for other conditions.

What is a Phase I/II Trial?

The atorvastatin experimental proof of concept trial for the treatment of symptomatic hemorrhage is a Phase I/II trial because it is assessing both safety and efficacy in one study. The safety part of the study is to determine whether the drug is safe for patients with cavernous malformation – it is previously known to be safe for the treatment of high cholesterol. This trial also seeks to establish the use of imaging biomarkers as measurements of the drug’s efficacy.

Using the atorvastatin trial as an example, with positive results, the study investigators will continue to phase III investigations and seek FDA approval, following the typical strategy diagrammed above.

What must I agree to do to participate in a trial?

A clinical trial is conducted according to a plan called a protocol that describes the types of patients who may enter the trial and the schedules of tests and procedures. Each trial has a unique protocol, so the requirements for participants vary from trial to trial. Each person participating in the clinical trial must agree, in writing, to follow the protocol—this is called giving informed consent.

It is important for volunteers to fully understand all of the information in the protocol before providing informed consent. Participating in a clinical trial is voluntary. Participants may choose to stop participating for any reason,

What should I ask before participating in a clinical trial?*

- What is the main purpose of this clinical trial?

- Does the clinical trial involve a placebo or a treatment that is already on the market?

- How will the treatment be given to me?

- How long is the clinical trial going to last and what will I be asked to do as a participant?

- What has been learned about the treatment used in the clinical trial and have any results been published?

- Do I have to pay for any part of the clinical trial? Will my insurance cover these costs?

- Is there any reimbursement for travel or other costs?

- Will I be able to see my own doctor?

- What will happen if I am injured during the clinical trial?

- If the treatment works for me, can I keep using it after the clinical trial?

- Can anyone find out if I’m participating in the clinical trial?

- Will I receive any follow-up care after the clinical trial has ended?

- What will happen to my medical care if I stop participating in the clinical trial?

- What research experience do the doctor and clinical trial staff have?

(*Response adapted from CISCRP.)

Where can I find more information about cavernous malformation clinical trials?

- Our Cavernous Malformation Patient Registry will send you personalized information about new clinical trials for which you may qualify.

- Clinicaltrials.gov provides a search tool that allows you to access detailed information about each planned and approved trial. Enter “cavernous malformation” in the search box to obtain a list.

- Summaries of cavernous malformation clinical trials are available through links from our Participate in Trials page.

- The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) provides general information about patient participation in clinical trials.

Last updated 3.26.23